Photo: Ed Wisneski on Sam Mountain border of Vietnam and Cambodia

Last October, the first time I saw Vietnam, a knot tightened in my stomach, much like the queasiness I felt 55 years earlier on the night of the first military draft lottery since World War II.

It was December 1, 1969. I was a sophomore at Dartmouth College, petrified by uncertainty, awfulizing my future. Instead of comfortably studying Macbeth and Monet on the scenic New Hampshire campus, I was wading through rice paddies with an M60 machine gun ready to mow down the Viet Cong. My fate depended on a raffle of 366 capsules containing the birth dates of all registrants born between January 1, 1944, to December 31, 1950.

My unlucky numbers were 4, 30, and 1950. The order in which your capsule was picked determined your place in line for a ticket to Vietnam. CBS News pre-empted Mayberry RFD to pick up a live feed from the Selective Service headquarters in Washington, DC, where correspondent Roger Mudd, in a hushed voice, described the drama of the capsules plucked from a glass bowl.

My birthday, April 30, was the 208th capsule chosen, high enough to dodge the bullets in Vietnam.

From Sam Mountain on the Cambodian border with Vietnam overlooking rice fields and the Mekong River, my thoughts wandered to the Vietnam Wall, always the most emotional monument for me in the nation’s capital. I could have been one of the 57,939 names who died or went missing in the Vietnam War, including my high school friend Mark Fitzgerald and Steve Baird, a classmate of my older brother Frank, who escaped deployment with something called atopic dermatitis.

How would the folks in Communist Vietnam treat an American? Most of the country’s population had no personal experience in the war. Was I more of a harmless tourist fattening their economy than an evil enemy? What about older Vietnamese who had connections to the “American War,” as they call it.

My answer came at the War Remnants Museum in Ho Chi Minh City (still called Saigon by many). It tells the Vietnamese side of the American War, focusing on American atrocities and conspicuously avoiding mention of any similar acts committed by the Viet Cong. The period of French occupation and disputes with China are also documented.

The former names of the museum reflected the thaw in animosity between Vietnam and the U.S in the past 50 years. In 1975, shortly after the fall of Saigon to the North Vietnamese, the Exhibition House for US and Puppet Crimes opened in the former US Information Agency building. Fifteen years later, it became the Exhibition House for Crimes of War and Aggression. Following the restoration of diplomatic relations with the United States in 1995 and the end of the U.S. embargo a year before, the name softened to the War Remnants Museum. This harmless name belies the brutal candor inside.

Some U.S. visitors don’t make it past the gift shop before dismissing the museum as propaganda. That’s evident and expected in a place owned and operated by the Vietnamese Communist government. There’s a section called “The World Supports Vietnam in Its Resistance to U.S. Aggression 1954-1975” with pictures, posters and a floor-to-ceiling montage of anti-war signs amidst a crowd of faces.

Quotes from U.S. politicians opposed to the war appear on the walls, especially from the most vocal critic, Senator Wayne Morse, and another from Senator Ted Kennedy, condemning American complicity in torture used by the South Vietnamese, who held 800,000 prisoners and was running out of room where to stockpile them.

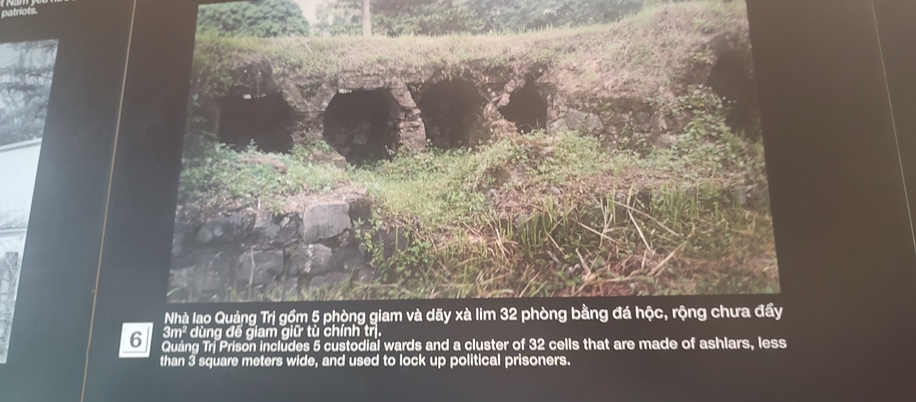

One photo shows tiny 33-square foot concrete prison cells carved out of a hill. Visitors who approach exhibits with open minds can’t deny the stark evidence of American brutality during the war. However, the only mention of the Viet Cong are statistics of losses on the walls.

Before climbing the steps to the museum, I weaved through “American POWs” in a crowded parking lot out front proudly demonstrating the spoils of the American War. Some of their names are H-1 “Huey” helicopter, F-5A fighter, M48 Patton tank, A-1 Sky-raider and A-37 Dragonfly attack bombers. Some of the aircraft decorated with non-standard “American Air Force” decals are South Vietnamese planes.

In the corner of the yard, a display of unexploded ordnance with their charges and/or fuses removed includes the BLU-82 “Daisy Cutter.” The 15,000-pound bomb developed by the United States earned its nickname by flattening sections of forest to create helicopter landing zones.

Contrasting this show of might is a 12-foot-tall French portable guillotine used in the colonial period to execute political and criminal offenders. The French brought it to Vietnam in the late 19th century and used it until 1960.

Inside, two hours grimacing at the graphic, compelling evidence of the enormous human and physical carnage from the war left me emotionally drained and deeply saddened. Strategically placed benches provide relief for those who only can take in the trauma in doses.

Two galleries are devoted to the impact of Agent Orange, the defoliant chemical used by the U.S. in its herbicidal warfare plan called Operation Ranch Hand. The U.S. obtained 20 million gallons during the war from nine chemical companies. It was named for the orange bands around the storage barrels.

Traces of dioxin (mainly TCDD, the most toxic of its type) found in the mixture caused major health problems and deformities on both sides. Rows upon rows of gruesome pictures of Vietnamese of all ages with disfigured faces and missing body parts graphically demonstrate how it still impacts victims 50 years after the war ended. To shock visitors and emphasize the culpability of the American perpetrators, there are jars of preserved human fetuses deformed by Agent Orange.

According to Vietnamese government, up to four million people in Vietnam were exposed to Agent Orange and up to three million have suffered illness were disabled or have health problems from exposure. The United States has described these figures as “unreliable,” while documenting cases of of leukemia, Hodgkin’s lymphoma, and various kinds of cancer in exposed U.S. military veterans. A CDC epidemiological study showed an increase in the rate of birth defects of the children of military personnel.

Agent Orange caused enormous environmental damage in Vietnam. Over 7,700,000 acres of forest were defoliated. Outside, an enlarged picture shows a boy standing in a field of “pick-up sticks” that once was a mangrove forest.

The lasting impression for me was the senselessness of war, especially the physical and psychological damage to soldiers and non-combatants that lingers to this day. By exposing the worst of war, perhaps the museum will promote peace.

How useful was this article ?

Click on a star to rate it!

Average rating 0 / 5. Vote count: 0

No votes so far! Be the first to rate this post.

We are sorry that this post was not too useful for you!

Let us improve this post!

Tell us how we can improve this post?