From the moment he learned to walk, Jules was a daredevil, always pulling off feats of derring-do. He came by it naturally. His father was a gymnastics instructor who also operated a swimming pool in the French city of Toulouse.

That early exposure to athletics ignited a passion in the boy that stayed with him all his life.

Jules especially loved showing off for others. A born entertainer, he eventually took his acrobatic skills to a whole new level. Literally. He arranged bars, ropes, and rings overhead and gracefully swung and twisted his way from one to the next. (He performed those feats above Papa’s pool, just in case something went wrong.)

People were impressed with the boy’s agility and ability. But his father had a different career in mind for his child. Sons didn’t argue with daddy’s dictates in mid-19th-century France, so Jules trudged off to law school.

He did well in his studies and passed his legal exams. But acrobatics held claim on his heart. He joined the famed Cirque Napoleon, named in honor of Emperor Napoleon III, who reigned in Paris at the time. It was an early forerunner of later extravaganzas like the Ringling Brothers & Barnum and Bailey Circus, “The Greatest Show on Earth.”

Jules quickly became a star attraction. He developed an act that both terrified and delighted the audience. It was a trapeze routine performed with three bars, which he debuted on Nov. 12, 1859. In that time before air travel was possible, he glided naturally and effortlessly high above spectators’ heads.

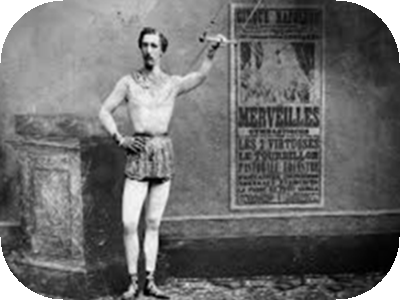

He even developed a special one-piece suit to wear for his performances. It was tight-fitting, streamlined to allow easy movement while also highlighting his toned, muscled physique. (More on that outfit in a moment.)

In 1862, now age 24, he married actress Silvia Bernini after having known each other for only six months. Things quickly soured. Two years later, he informed his wife by telegraph that he wanted a divorce. She rushed to him in Paris. The reunion resulted in ever more fighting. Silvia melodramatically cut off her hair and mailed it to Jules, then tried to drown herself in the Seine River. Both the suicide attempt and marriage failed.

Jules took his act across the English Channel. He wowed London audiences at the West End’s fashionable Alhambra Music Hall in Leicester Square.

You would think the promotion of his performances would play up his routine’s stress, difficulty, and high-risk aspects. But it didn’t. Circus ringmasters in later years would proclaim the “death-defying” nature of acrobats’ abilities. Instead, advertising for Jules’ routine always emphasized the “ease and grace” of his trapeze work.

That caught the attention of British lyricist and singer George Leybourne, who was looking to capitalize on the trapeze craze’s popularity. Together with composter Gaston Lyle, they published the following song in 1867 as a tribute to Jules:

“He’d fly through the air,

with the greatest of ease;

That daring young man,

on the flying trapeze.”

The song was an instant smash hit, and the fact that we still know it 158 years later speaks much about its durability.

As you might guess, Jules didn’t live to a ripe old age. However, didn’t die as a result of a dreadful fall, either. He passed away due to illness (most likely smallpox) at age 32 in 1870.

Though his life was short, his legacy lives on through the many acrobatic artists who still enthrall and delight us.

And through his clothes, too. That tight one-piece outfit he created over a century and a half ago remains a big seller today.

And it’s known by the name of the man who invented it. Because Jules the acrobat was named Jules Leotard.

How useful was this article ?

Click on a star to rate it!

Average rating 5 / 5. Vote count: 5

No votes so far! Be the first to rate this post.

We are sorry that this post was not too useful for you!

Let us improve this post!

Tell us how we can improve this post?